Overview of the Galleries

The Historic Science Centre is well worth a visit, as it reveals the remarkable story of this unique site and the Parsons family through the wonders of early photography, engineering, and astronomy.

This captivating collection of stories, heritage, and fascinating artifacts enriches your experience before you head out to explore the demesne.

The Historic Science Centre is housed in the former stable block, designed by the 3rd Countess, and spans over seven galleries.

In addition to the science galleries, the building includes our welcome reception, toilet facilities, café, offices, gift shop, and the Copper Tree Gallery, which is used for events and exhibitions.

Read More

Discover the hidden answers by completing the Gallery Challenge which is a wonderful family activity and suitable for those aged 9 to 12. The Historic Science Centre spans across both the ground and first floor of the reception. A wheelchair accessible lift can be found at the end of Gallery 2.

Astronomy

The Astronomy of Birr Castle is one of its greatest attractions and, in many ways, one of its surprises. It is unusual for a Castle in the centre of Ireland to have become a great centre of astronomical discovery. However, in 1845, the 3rd Earl of Rosse built the biggest telescope in the world and it remained so for 75 years. Here you may see the great telescope – the Leviathan – still standing in the middle of the park with its huge 52 foot (15 metres) long tube with a diameter of 6 foot (1.8 metres).

Read More

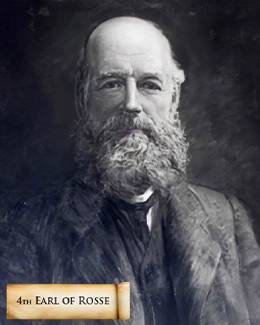

William, the 3rd Earl of Rosse was able to build this telescope with the help of his wife Mary’s fortune. It was a great engineering feat because he had to work out the ability to raise and lower the immense tube, and also to cast the mirror, or speculum, himself. It took many experiments to find the right combinations of metal to use for this. The metal was then heated in a furnace in the moat by turf (or peat) from the bogs which comprised much of his estate. The next problem he had was in cooling the speculum. The first two mirrors cracked as cooling happened too quickly. He eventually made two mirrors which were inter changed and removed for polishing as the damp caused them to mist over. This in itself was another engineering feat, and a small railway line was built to transport the massive mirrors to and from the workshops for polishing. One of the major discoveries with the telescope was the spiral nature of the nebulae. The great mirror was the first to be able to see that many of these were spiral in shape. What Lord Rosse was seeing were in fact galaxies. The famous M.51 whirlpool galaxy is the classic example of this and we have commemorated it with a spiral of lime trees which visitors can walk around. Astronomy at Birr continued with the 3rd Earls son, Laurence, the 4th Earl. He was especially interested in the moon and invented a machine called the Lunar Heat Machine which measured the heat of the moon. The accuracy of this was proved to be correct with the landing on the moon in 1969. The machine is on display in gallery 4 of Ireland’s Historic Science Centre.

Engineering

Charles Parsons was the youngest child of William, 3rd Earl and his wife Mary. They had 4 sons who grew to adulthood, and Charles was some 15 years younger than his eldest brother who became the 4th Earl. All four of William’s sons were brought up among construction, engineering, and work on the telescope so Charles was involved in practical work in the workshops at an early age. The boys were educated at home here in the Castle with their brothers until Charles left for Trinity and then Cambridge, where he got an honours degree at St John’s College.

There was a long tradition of what might be called engineering in the family. His father, William. self-taught in that field, produced the mechanics for lowering and raising the telescope. Charles is best known for his invention of the steam powered turbine which was used eventually to power the engines of ships. His invention of a turbine engine in 1884, making cheap and plentiful electricity possible, revolutionised marine transport and naval warfare. This turbine changed the world, and Charles can be said to be the father of the jet engine.

Charles Parsons realised the potential of his new turbine to power ships and in 1893 he, along with five associates, formed the Marine Steam Turbine Company. It was decided that the first experimental vessel be named Turbinia. The vessel was 104 feet (37.8) in length but only had a beam (maximum width) of 9 feet (3.2m). Turbinia was built of very light steel by the firm of Brown and Hood, based at Wallsend-on-Tyne. Eventually improvements resulted in a top speed of over 34 knots, equivalent to 40 mph (64 kph). Turbinia completed her high speed trials in the North Sea.

By 1897 Charles Parsons’ Turbinia had proved herself, now all her inventor had to do was sell his new idea to the British Admiralty. In an audacious sales pitch, he arrived uninvited at the Navy Review for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee at Spithead on June 26th, 1897. Among those present would be the Prince of Wales, representing the Queen, Lords of the Admiralty, as well as a complete cross section of the British establishment of the time.

Also at the event would be foreign dignitaries and ambassadors. With its ability to reach speeds of 34 knots (60 kilometres per hour) Turbinia was so much faster than anything else on the water that she could not be caught. Charles hoisted a red pennant and took off in a high speed burst between two lines of large ships. The Royal Navy had set up patrol boats to keep ships in line and to prevent antics such as the Turbinia was to perform. The patrol boats were completely unable to catch her. Charles cut it very fine and came perilously close to some of the ships and patrol boats in the display. In one incident, Turbinia nearly collided with a French yacht and just managed to scrape past her bow. Turbinia had certainly made her presence felt as the fastest boat in the world. Charles Parsons had made his point, not only to the Admiralty but also to the foreign naval representative present at the demonstration.

Mary Rosse and her Dark Room

Mary, the wife of the 3rd Earl, was born in 1813 at Heaton Hall, near Bradford in Yorkshire, daughter and co-heiress with her sister, of a wealthy landowner. Her father, having no sons, brought up the girls with an excellent education, which included mathematics and scientific subjects. Mary and William married in 1836. William, was already greatly interested in astronomy, and had ambitious plans to build the biggest telescope in the world. Mary’s money would allow him to do this. She too was interested in the sciences and was well suited to William and understood his plans.

The marriage was a happy one. Their eldest child was a daughter, Alice, and then came Laurence, their heir, later to be the 4th Earl, and by 1848 they had three more boys, William and John and Randal. Sadly Alice their only daughter died of rheumatic fever aged eight. After Randal came two more boys, Clere and eventually Charles the youngest who was to be the great engineer. But in 1855 her second son William died aged just 11, and little more than a year later John, her third son, now too aged 11, also died.

Read More

The deaths of children were a constant spectre in the lives of the Victorian households as so many children did not survive childhood illnesses. Between these children were other births, although these babies did not live more than a few days. Altogether of her eleven children only the four boys, Laurence, Randal and the two youngest Clere and Charles lived to grow up.

Mary's Photography

Mary had started, perhaps tactfully, by photographing her husband’s great passion, the telescope, but she soon moved on to subjects of her preferred choosing, photographing her children and portraits of some of the eminent visitors to Birr Castle. Though sadly very few of Mary’s photographs have survived, those that have show great skill in composition.

The skill with which she composed these, displayed Mary's sensitively trained eye. No detail was overlooked and though exposure, often to twenty seconds was necessary, she achieved spontaneity in her work.

Read More

The earlier collodion process followed on from Fox Talbot’s negative-positive calotype process, and was the forerunner of modern photographic processes. It was followed by the wet collodion process with which Mary now worked. This was quite difficult, even stressful, in that it required sensitisation immediately before exposure, and development had to be done within the next ten minutes before the coating dried. Although most of Mary’s photographs that we know of were by the collodion process, which was her preference, and became well known for, the wax paper process which permitted the photographer to keep the sensitised material for several days prior to exposure. With this waxed paper process she was able to travel with her equipment and even took photographs on board the family yacht the Titania. Unusually for photographers of the time, she also enjoyed landscape photography and took several of town, the river and views of the castle. Sadly none of these paper negatives have yet come to light. Mary’s work earned her the Photographic Society of Ireland’s first silver medal. She was the first person, male or female to whom it was awarded. The beautiful medal can be seen on display in the Science Centre. She was a member of other photographic groups including almost certainly the Royal Photographic Society in England. And she was the first lady member of the Dublin Photographic society.

The Dark Room

The Dark Room is believed to be the oldest dark room in Europe – indeed the world. It was established as early as the 1840s when the 3rd Earl began his photographic attempts.

Mary used the room extensively for more than a decade, as did her son the 4th Earl until 1908. The room was a photographic time capsule, having lain untouched until 1983, and its rediscovery was an exciting date in the history of photography.

Read More

The Dark Room has now been moved completely and re-created in the Science Centre, even the floor and ceiling with its trap door was moved. Now you can see it exactly as Mary Rosse left it, with cupboards full of chemicals and the old lead sink.